Making truth powerful;

Making power truthful

The mounting fiscal pressures and debt burden plaguing most African countries have seen increased vigour in efforts to enhance domestic resource mobilisation. These efforts have taken the form of modernised tax systems, streamlining tax policies and establishing structures and guidelines for minimising/curbing illicit financial flows. Whilst there have been notable successes, as demonstrated by increased tax revenues in countries like Kenya, many countries are yet to figure out how best to tax a potential source of revenue – the informal sector.

The informal sector forms a large proportion of the economy in many developing countries. In sub-Saharan Africa, the sector contributes between 25 and 65 percent of GDP.[1] Additionally, it is estimated that the informal sector provides employment for more than 70% of the population in Sub-Saharan Africa.[2] In Kenya, the informal sector has grown substantively over the years and is estimated to account for 35% of Gross Domestic Product[3] while in Uganda and Tanzania, the sector covers more than 50% of GDP.[4]

Size of informal sector in Sub-Saharan Africa | AfDB

The massive contribution of the informal sector to the economy is attributable to its free nature that allows for easy entry and innovation for anyone capable of monetising their skills. The sector also provides an alternative avenue for the trade of goods and services affordably, especially for middle and low-income earners.

Whilst the size of the informal sector portends the potential for broadening the tax base and bridging fiscal deficits, the nature of the informal sector makes it challenging to harness this potential. The architecture of the sector comprises largely unstructured and unregistered businesses, which makes it difficult for the government to capture their contribution to the economy using mainstream tax structures. The fluid structure of the sector means informal workers are not subjected to paying VAT as is the case with formal businesses. In essence, the tax compliance structures adopted for formal businesses are not effective in taxing the informal sector.

Over the past years, revenue authorities have been keen to streamline taxation frameworks to bring the informal sector into the tax bracket. These have mostly been in the form of a presumptive tax scheme, which manifests as a simplified tax schedule that aims to encourage record keeping and tax computation. Despite the various efforts made, the level of tax compliance among traders remains low. In Kenya, for instance, high administrative costs, low awareness and understanding of the taxes, mistrust and weak structural dialogue between the informal sector and government have contributed to low levels of tax compliance.[5] The rising cost of living also discourages most actors in the informal sector to adhere to these structures and provisions, as most seek to sustain their working capital, amid dwindling profit margins.

Jua Kali workers | Source: Business Daily

In Uganda, the presumptive tax system in place for the informal sector takes the form of a top-down approach where tax authorities impose taxes on businesses and force them to comply. The current relationship between tax authorities and taxpayers resembles that of a “cops and robbers” scenario. This has continued to erode the trust of taxpayers in government, particularly owing to the fact that, to the majority, government has failed in its mandate to deliver public goods and services effectively.[6]

In Tanzania, implementation of the presumptive income tax scheme applied to street vendors has been affected by the lack of a proper regulatory framework to accommodate the use of urban spaces. The presumptive tax requires street vendors to have a business license. But to obtain a business license, one needs a physical address whereas, street vendors operate in undesignated areas. The government, therefore, needs to collaborate with vendor associations to set up good working environments to accommodate street traders.[7]

These cases point to the need for a more pragmatic approach from the government to capture the informal sector within the tax bracket. This should begin by first strengthening communication and engagement with the informal sector actors to foster trust and incentivise them to fulfil their tax obligations. There is also need for more transparency with regard to government budgeting and the utilization of tax revenues.

It is also important to note that taxing the informal sector is not a ‘one size fits all’ affair. As such, efforts to tax the informal sector should begin with defining what the informal sector comprises. The International Labour Organisation uses various operational criteria such as registration, licensing, taxation and labour standards to define the informal sector.[8] Borrowing from this, the informal sector encompasses activities from petty traders operating in the streets of urban centres. For instance, traders involved in the sale of second-hand items like clothes, some in the business of shoe shining, street vendors, carpentry, vegetable selling, repair, construction work among others. The informal sector also comprises of better off ‘urban professionals’ such as doctors, lawyers, architects etc. who operate as unregistered businesses.

However, the definition should be further adapted to fit specific contexts. This definition is critical in establishing appropriate thresholds distinguishing those earning too little to meet VAT or income tax thresholds and those ‘hiding’ in the informal economy to evade taxes. Having a clear definition will chip into realising tax justice, bearing in mind that the informal sector already bears much of the tax burden through indirect taxes such VAT.

Lastly, taxing the informal sector should be coupled with critical reforms to curtail the loss of revenue such as reduction of loss in tax revenue through tax incentives and curbing illicit financial flows.

Until governments figure out the right taxation framework and enforcement mechanisms to ensure players comply, the sector continues to remain an untapped gold mine that has the potential to strengthen domestic resource mobilisation to fund government expenditures.

[1] https://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/Publications/REO/AFR/2017/May/pdf/sreo0517-chap3.ashx#:~:text=The%20informal%20economy%20is%20a,of%20total%20nonagricul%2D%20tural%20employment.

[2] https://www.un.org/en/ecosoc/integration/2015/pdf/eca.pdf

[3] https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3.sourceafrica.net/documents/118220/The-informal-sector-and-taxation-in-Kenya-IEA.pdf

[4] https://www.repoa.or.tz/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Taxing-the-informal-sector.pdf

[5] https://ijlhss.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Informal-Sector-and-Taxation-in-Kenya-Causes-and-Effects.pdf

[6] http://jota.website/index.php/JoTA/article/view/232/181

[7] https://www.repoa.or.tz/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Taxing-the-informal-sector.pdf

[8] https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---emp_ent/documents/publication/wcms_820312.pdf

Most developing countries have failed to collect sufficient revenues to finance their national budgets, hence have had to rely on borrowing to finance their development and maintain other spending commitments. As a result, there has been an exponential rise in public debt stocks, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa over the past 10 years. According to a new International Debt Statistics 2022 report published by the World Bank, the debt burden of the world's low-income countries rose by 12% to a record $860 billion in 2020. For instance, in Kenya, the Central Bank reported that the country's public debt stock stood at Ksh.8 trillion which is about 68.2% of its nominal GDP as of September 2021.

Economists and development practitioners have demonstrated that the unprecedented trend in public debt acquisition has had negative implications on the economy. It exacerbates poverty and inequality, and limits broad-based and sustainable development as witnessed in many Sub-Saharan African countries. Essentially, debt repayment diverts funds from social services and key public investments and may lead the government to implement unfair tax policies to meet debt repayment revenue demands. Domestic borrowing also crowds out private sector borrowing, thus hampering investment and output growth.

Relationship between public debt and economic growth

Cognizant of these consequences, there is thus a need for openness and public scrutiny of the conduct of public debt policy decisions taken by the government and accountability for expenditures of resources obtained through debt mechanisms. This requires greater debt transparency that guarantees access to credible information on debt. Adequate and reliable data on public debt is important because it allows policymakers to make informed decisions about future borrowing with an accurate understanding of the cost and risks of the existing debt portfolio. It also enables creditors and rating agencies to understand borrowers' debt sustainability challenges, accurately price debt instruments and estimate comparability of treatment in the event of debt restructuring. Furthermore, the citizens can use the information on public debt to hold their governments to account for the debt they take on, thereby facilitating better governance, increasing accountability, and helping to counter corruption.

However, with the rising public debt levels and the emerging role of non-traditional lenders, serious concerns have been raised about debt transparency in many developing countries. Debt statistics and reporting remains incomplete or non-comprehensive. In many instances, debt agreements have included confidentiality clauses, which limit overall debt transparency. A report by the World Bank highlights that close to 40% of low-income developing countries had never published data on debt or had never updated the information in the last two years as of November 2021.

Several factors hinder countries from compiling and reporting comprehensive data on public debt. Capacity constraints arise as a major hindrance in ensuring an efficient debt data reporting system. It limits the ability of low-income developing countries to report comprehensive public debt data. Human resources and IT infrastructure are inadequate, thus constraining the capacity to collect, compile and disseminate debt statistics. Considering that other development objectives are prioritized more than higher-quality statistics, investing in statistical capacity is difficult to achieve. Debt management offices have insufficient ability to collect debt information, limiting data collection to only the central government. Moreover, governments may not have the adequate legal capacity to evaluate loan contracts appropriately.

Secondly, the definition of public debt under national laws in many jurisdictions in the developing world is sometimes unclear. Legislations define public sector debt coverage narrowly, meaning debt compilers do not have the legal mandate to collect debt statistics from broader public agencies. For instance, in some jurisdictions, the definition of public debt only covers central government without incorporating debts accrued by outside entities such as public corporations. Because of differing definitions of debt and recording errors, debt data available often show variations equivalent to almost 30% of a country's GDP.

Thirdly, weak administrative and political governance often hinder proper debt recording, monitoring, and reporting. Sometimes, senior administrators and political managers lack the incentive to produce correct debt statistics because there is a lack of demand for reliable, timely, and comprehensive data, limited public scrutiny, and limited integration with other public finance management systems. Some governments have also chosen not to disclose public debt data to maintain confidentiality around politically sensitive issues, such as security investments or access to natural resources. An opaque debt environment provides an opportunity for government operatives to obtain personal gains. This is further complicated by the fact that audit of debt management operations is rare in developing countries. These undermine efforts at national levels to pursue more comprehensive debt statistics coverage, adopt modern IT infrastructure, and strengthen legal backing with strong enforcement mechanisms in the event of noncompliance.

Also, due to domestic interest, often motivated by political objectives, some borrowing countries have chosen to hide the true extent of indebtedness or the collateral granted to selected creditors to avoid a higher debt cost in the short term. For example, a leaked report from the auditor general in 2018 sparked rumors that Kenya had staked the port of Mombasa as collateral for the Chinese-funded Standard Gauge Railway project. Debtors may also be impelled to circumvent policies that may impact borrowing costs or loan availability, such as fiscal rules and borrowing limits. On the other hand, lenders may conceal crucial data to acquire borrowers' favor to facilitate lending operations or promote broader business/politically strategic objectives. Lenders also try to avoid disclosing financial or legal terms to competitors, hence the need to keep lending terms secret.

Investments in debt data transparency enhance improvements in accountability within debt management practices. This brings benefits in the long run, including reductions in the costs of credit. A study by OECD on Emerging Market Risks and Sovereign Credit Ratings showed that transparent debt management practices result in higher credit ratings and stronger investor appetite (investors prefer investing in countries where they know the stock and composition of debt), ultimately reducing the cost of external borrowing. On the contrary, low levels of debt data disclosure may lead to debt mispricing and/or significant fiscal and debt rollover risks. In Zambia, for example, the uncertainty around public debt coverage and lags in reporting led to speculation around the true level of indebtedness and a sharp increase in bond yields. In 2016, the discovered state-backed "hidden loans" that were not approved by parliament halted Mozambique's development progress. These loans breached the International Monetary Fund Program at that time. Consequently, the IMF and other development partners outrightly suspended budget support.

Transparency in debt management also forms an integral component of governments’ efforts to restructure debt. When negotiating debt restructuring, lenders require accurate information on the size and composition of the borrowers' debt portfolio and the level of debt relief needed to restore debt sustainability. The absence of accurate and comprehensive data delays debt restructuring since reconciliation has to be undertaken between debtor and creditor records.

Accountable sustainable public debt management can help a country maintain sovereignty over domestic infrastructure and natural resources. Some countries have had to make steep concessions or cede control of their resources to creditors like China because of non-transparent loan repayment obligations. Sri Lanka, for example, had to surrender its strategic port to Beijing in 2017 after it failed to pay off its debt to Chinese companies.

Port of Hambantota, Sri Lanka

Ultimately, adequate, accurate, and accessible data on public debt has a critical role in promoting accountable and prudent public debt management. This can help prevent debt crises (and economic hardships that may come with them) and facilitate effective use of resources obtained through public debt mechanisms. The lack of credible information on debt obligations makes it difficult for international financial institutions to accurately estimate countries' debt burdens, provide recommendations to limit debt distress, and determine appropriate debt amelioration solutions. For non-state actors like Civil Society, media, and experts, challenges related to access to public debt data limit their ability to analyze, scrutinize and report on debt situations in their respective jurisdictions. This hampers transparency and accountability for public debt policy decisions taken by governments. It also limits the inclusion of alternative ideas, voices, and aspirations of citizens on whose behalf debt is acquired, and who bear the responsibility for repaying debt.

Cognizant of these challenges and dynamics, governments must be challenged to make information on public debt available to the public to facilitate scrutiny and enhance good governance and accountability. Lenders must also be brought to account for under-dealings that limit public knowledge and conceal information on debt agreements they sign with recipient governments. They must be encouraged to avail information where recipient governments fail to promote transparency. Civil society can help improve public understanding of debt issues by conducting public education and advocating for more debt transparency. This can include public litigation to compel the government to make public debt information available. Academia and experts can also play a role in conducting diagnostic studies, research, and analysis of debt situations and their implications for economic development, fiscal justice, and overall sustainability.

Following the debt binge over the last couple of years, Kenya is set to spend KSh. 1.36 trillion towards debt repayment annually starting FY2022/23 going forward[1]. In light of this, debt repayments will consume approximately 65% of taxes. This signals that the country has a narrower fiscal space for balancing the budget and achieving equitable and sustainable economic development.

Nonetheless, it is notable that the Kenya government gives away or foregoes a lot of revenues that appears not to square out with its fiscal challenges. For instance, a 2021 Tax Expenditure Report published by the National Treasury highlights that Kenya has foregone on average Ksh383.9 billion worth of revenues between 2017 and 2020 to tax incentives. These revenue losses compare to equitable share revenues allocated to all counties in FY2020/21[2]. Also, the report estimates that the country loses up to 6% of GDP through generous tax incentives. A 2017 publication by the IMF set the cost of tax incentives at KES 478 billion, a figure that accounts for 5.3% of the country’s GDP.

What then does this mean for fiscal justice in Kenya? At what cost is the government dishing out tax incentives for individuals and corporates established in Kenya? Is there room for better management and administration incentives/expenditures to ensure the economy reaps the most? Are tax expenditures as efficient as argued by the government?

World over, governments leverage tax incentives as a fiscal policy tool targeting to spur economic development by attracting investments. Tax incentives are preferential tax treatments accorded to specific segments of taxpayers. In Kenya, tax expenditures manifest in the form of tax deductions, credits, tax exemptions, deferrals, and tax rates designed to benefit specific economic activities or taxpayer groups. Such expenditures are considered as a basis for financial support from the government to both individuals and corporates established in the country.

The government argues that existing tax incentives have positively impacted Kenya’s outlook as a favorable investment destination in East Africa and the larger Sub-Saharan Africa region. However, pundits have argued that the net effect of tax incentives/expenditures in the country is negative, with the revenues forgone far outweighing the volume and value of investments resulting from the said preferential tax treatments. Further, tax incentives are argued to be shrewd in secrecy and tend to receive less public scrutiny.

The frameworks that dictate the criteria for design and determination of beneficiaries of tax incentives are neither open nor inclusive as demanded by law and prudent public finance management. It remains unclear to what extent these preferential tax treatments have contributed to spurring investments and creating employment in the country. With limited transparency, some have argued that the existing tax incentives in Kenya benefit particular interest groups and advantaged firms, especially Multinational Corporations (MNCs).

As such, the utility and effectiveness of the existing tax incentives offered under the current tax regime have been a subject of debate, particularly considering that the foregone revenues would be useful in bridging the widening budget deficits and dealing with the ensuing public debt problem in the country.

The questions surrounding the utility of existing tax incentives in Kenya demand that relevant stakeholders revise the architecture of formulating tax incentives in the country to promote more transparency and accountability. This demands goodwill of various stakeholders. Policymakers need to enact suitable guidelines that inform how tax incentives are structured and the criteria for qualifying for the said incentives.

Relevant government agencies, particularly the Kenya Revenue Authority and the National Treasury, need to promote transparency and enhance multiagency cooperation. This can be demonstrated by adherence to provisions of the constitution and associated laws, encouraging inclusion and multi-stakeholder engagement in applying tax incentives, and maintaining openness with regards to application of tax incentives in the country by easing accessibility to data.

Currently, the utility of existing tax incentives in Kenya remains unclear, particularly with regards to attracting investments and creating employment opportunities in the country. Coming at a time when the tax regime in the country has been criticized for being punitive to businesses and citizens with increased taxation, tax incentives need to be streamlined to clearly demonstrate their adequacy, usefulness and overall efficiency to the economy.

A move towards positive reforms demands proper engagement and coordination by government through the National Treasury, KRA, Parliament, Auditor General, and the Office of the Controller of Budget, Civil Society, Private Sector, Researchers/Experts, and Media.

A good place to begin is rigorous analysis of the country’s framework of tax expenditures driven by government data from KRA, the National Treasury and the National Bureau of Statistics. Such analysis can shed light on sectors of the economy where incentives/expenditures are incurred, segments of the population (in terms of income levels) that benefit most, the balance of costs and benefits for local and international businesses among other pertinent considerations. That way, it can be possible to tell for sure whether the revenues forgone by KRA/Treasury are warranted when compared with the benefits accrued.

Civil society, academia and media can also play a role in conducting complementary analysis and providing supplementary information generated from monitoring and reporting on the economy.

[1] https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/bd/economy/debt-payments-surpass-state-running-expenses-3762312

[2] https://www.treasury.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/2021-Tax-Expenditure-Report.pdf

Over the last decade, social media has increasingly been used as a source of information - a mechanism for creating and conveying content online. While this has greatly enhanced access to information and freedom of expression, there has been a dramatic increase in the volume of disinformation and other forms of harmful content. This has been exacerbated by the increased uptake and consumption of content on social media. It is estimated that, in 2021 alone, more than 4.5 billion people globally had access to the internet and used social media to share information. Considering the architecture of the internet and with more than half the global population being active users of the internet, the pace at which information spreads has become increased and audiences widened.

While this ability to share information with ease is a marker of global progress, the world remains exposed to the constant threat of harmful content. The adverse impact of misinformation and disinformation threatens social cohesion and core democratic principles.

Most recently, social media has been an indispensable tool in politics largely used in campaigns. And with unrestricted access and weak or lack of effective regulations of digital technologies, the effects of fake news and harmful online content have been manifested across the world, even in the most advanced democracies. For instance, disinformation and fake news regarding the outcome of the 2020 presidential elections in the United States was alleged to have contributed to the insurrection at Capitol Hill on January 6, 2021. Also, in the United Kingdom, observers have argued that the 2015 Brexit referendum vote was significantly compromised by agents that actively misinformed the British population. Such examples of the harmful effects of fake news and other polarizing information on societal cohesion and democratic principles have been witnessed across the world, including in Indonesia, the Philippines, Colombia, Germany, Italy and Spain, among others.

The African continent, particularly Kenya, is no stranger to the consequences of fake news, hate speech and other harmful content spreading online. The 2007 general elections in Kenya were accompanied by violence fueled by hate speech. In 2017, polarizing information put the country at the brink of violence. Addressing the spread of misinformation and other forms of harmful content in 2017 was more challenging, considering the complexity brought about by the use of social media and the internet to propagate such harmful content. In Kenya today, more people, especially youths, have access to social media and the internet than in 2017. With the general elections just months away, it means that Kenya’s democratic principles are now put under extreme test and threat, granted the feisty nature of the country’s politics.

Considering the realities of online harmful content and the danger it poses for democracy, societal tranquility and sustainability of established norms that bind communities together, countering fake news and other forms of harmful content shared across both online and offline platforms is now critical. There is a need for concerted efforts by both state and non-state actors to address the threats and harms posed by harmful content. The potential role of social media in peace building and encouraging dialogue needs to emphasized and more focus put into utilizing digital technologies to promote peace narratives.

In contributing to efforts to promote peace and fight fake news in wake of the upcoming 2022 general elections, UNESCO is implementing an EU-funded project on Social Media for Peace in Kenya. Through the project, UNESCO seeks to empower youth in the country to be more resilient to harmful content.

The Africa Centre for People Institutions and Society (Acepis) is working together with UNESCO and the EU in these endeavours. During the months of February and March 2022, Acepis will identify and train at least 300 young people drawn from 47 counties in Kenya on Media and Information Literacy (MIL) and how to use MIL skills to be more discerning creators and consumers of content online. The series of trainings targets to equip youth in Kenya to identify, counter and report online harmful content. This shall be augmented with knowledge brokering sessions where representatives of prominent social media platforms shall engage youths on their Community Guidelines in relation to harmful content.

#SocialMedia4Peace campaign in Kenya facilitated by Africa Centre for People Institutions and Society (ACEPIS)

The training will be complemented by an online awareness-raising campaign that will be run concurrently with the trainings in February and March 2022. The online campaign will target to produce and share messages on how to counter harmful content in Kenya, and promote peace-building narratives on social media. The campaign shall include production of blogs, hosting tweet chats, live video chats and dissemination of short videos on how to counter harmful content online.

The overall objective of these and other similar efforts is to build a society that is resilient and able to diffuse fake news and other forms of harmful content across online and offline platforms, during and beyond the 2022 the electioneering period.

Acepis invites any interested actors that work in this space or share similar mandates for partnerships and collaborative arrangements.

There exist numerous advocacy campaigns promoting gender equality and fairness to allow women to have equal opportunities in getting wage and salaried jobs. Following the recently celebrated International Women’s Day, we reflect on where the East African region stands with regard to the proportion of women in wage and salaried work, and the opportunities to explore in order to bridge the gap.

Also Read: In East Africa, Women Still Lag Behind in Labor Force Participation

Wage and salaried jobs provide a stable and reliable source of income hence, in most instances, they are dependable for the economic development of individuals and households. In this section, we compare the proportion of women in wage and salaried jobs, compared to women. Similar to the Labor Force Participation Rate, women make up the minority of wage and salaried workers in the region. It is notable that almost across all the countries in East Africa, the % of males in paid employment jobs almost doubles that of females. This is illustrated in the chart below.

There was an issue displaying the chart. Please edit the chart in the admin area for more details.Data Source: World Bank/World Development Indicators

Data released by LinkedIn reveals the fact that, globally, while women stand a higher chance of being employed by up to 16% compared to men, they are 16% less likely to apply for a job they are qualified for, despite them viewing the same number of jobs as men.[1] They are also less likely to ask for a referral for a job compared to men. This one of the factors that help explain the low percentage of women in salaried work. Instability in some countries, weak economies, retrogressive cultures that are pro-patriarchy and general lack of effective and progressive policies that ensure equal representation of women in the workplace are other underlying factors that discourage or hinder women from joining the wage and salaried workforce.

Also Read: More needs to be done to empower women!

To address these disparities, there is a need for further empowerment of females to ensure that they gain access to quality education, which puts them at a better place to compete for opportunities of employment. Additionally, there is a need for corporations and the government to establish policies that ensure women receive equal working opportunities, fair pay and opportunity for career growth, as men.

[1] https://business.linkedin.com/talent-solutions/recruiting-tips/gender-balance-report#

12.01.2020: A 24-year old walks out of one of the departmental offices at Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture Technology.

A smile is on her face and a brown envelope in her hand - her life’s work. She has toiled for about 20 years for this. Education is the key to success, her teachers said, and her parents echoed. Finally, she is holding the key - a Bachelor’s degree in Biostatistics. The only thing left now is to open the door to success; get a good job with good pay. Well, she has got the key, how hard can it be?

Unfortunately, she is not the only one. About 800,000 young people enter the Kenyan labor market each year. Therefore, the answer to her question is: “It is hard.”

It is not hard because job hunting is a daunting task – though it actually is, in real life. It is hard because of rampant unemployment in Kenya, which means many people in need of jobs cannot find them.

PHOTO | NMG

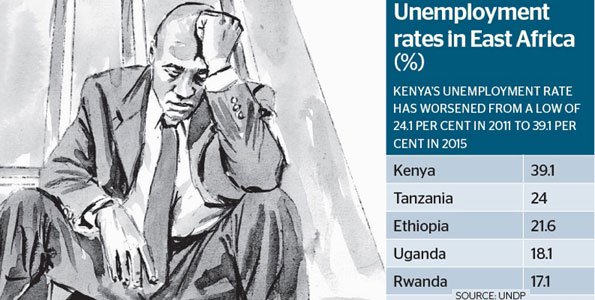

According to the United Nation’s Common Country Assessment Report, the rate of unemployment in Kenya stood at around 40% in 2018. More startling, however, is the proportion of unemployed youths: about 80% of the unemployed population are youths. For every 10 jobless Kenyans, 8 of them are youths, aged between 15-34 years of age. They are not unemployed because they are lazy, an argument put forth so many times, but due to the scarcity of jobs.

The World Bank estimates that the Kenyan economy registered substantive growth between 2003 and 2014 with average GDP growth rates of 2.5 percent every year. Besides, employment rates also increased by 4.5 percent each year between the years 2006 and 2013. However, a report by SAMUEL HALL and the British Council on Youth Unemployment in Kenya, 2017, shows that the rate of youth unemployment has been increasing at a rate of 42 percent since the year 2000. This is a clear indication that the economy has not been creating enough jobs to absorb young people joining the labor market every year. Despite increased rates of unemployment, over 7,000 workers had been sacked in a wave of massive layoffs by the end of 2019.

PHOTO | BD GRAPHIC

More petrifying being the misery that comes with unemployment. Do you remember the story of Rebecca - the 20-year-old woman who had lost her job, got kicked out of her home, had no money and ended up giving birth unassisted in Uhuru Park?

What about Alfred Kibet Kirui? The university graduate who posted on Facebook, threatening to commit suicide owing to his job-hunting efforts not bearing any fruits. There is also the story of the young man, tired of unsuccessful job hunting, decided to hold a placard near State House, begging the President to help him join the Kenya Defense Forces. These anecdotes of agony caused by unemployment are unending, to say the least. We have had numerous cases of suicide attempts, increased criminal activity, and prostitution - all because of unemployment.

Youth unemployment in Kenya is, to put it simply, a disaster. It has been for years now. It is so bad, Antony Aluoch, a Kenyan legislator, wanted it declared a national disaster! Well, isn’t it about time?

Even some of those with jobs find themselves in professions they have not been trained in. A nation's economy flourishes when individuals work in a market that matches their skills. This phenomenon of job mismatch results in massive underemployment, hence wastage of abilities considering the investment towards education.

Also read: Is Africa Really Ready for Women Leadership?

In the wake of this massive job crisis, the Kenyan government set out to address the issue through a number of initiatives. One of them was the Ajira Digital Programme that sought to equip youth, especially university students, with online work skills from which they can earn a living. There is also the National Youth Service that recruits and trains youth in various fields, including paramilitary, engineering, fashion, and design, to name but a few. The government has also launched a myriad of programs to curb unemployment by encouraging youth to embrace online self-employment.

However, the effectiveness of these initiatives is a point of concern to many people seeing that unemployment remains an issue. The other unanswered question is: whether the government is doing enough to create jobs for youth. Training the youth in various fields, equipping them with the necessary skills and encouraging them to embrace self-employment is important and necessary, but what happens after that?

Finland took over global news towards the end of 2019 with the election of its youngest-ever prime minister. Not only is Sanna Marin, the PM-elect, a young woman, she is also backed by a cabinet that majorly comprises young women – most under 40 years of age! A breath of fresh air, don’t you agree?

This is just one of the many examples of women globally, who have risen to highest echelons of leadership in both political and corporate spaces. The Finnish cabinet is a perfect depiction of the power and leadership capabilities that women have. A lot has been done over the past decade towards women empowerment – from equity in distribution of resources to equality in access to opportunities. This has greatly contributed to the rising number of women in leadership. A lot more remains to be done, with gender equality designated as one of the Sustainable Development Goals that the world is gunning for by the year 2030.

Left to right: Finland's Minister of Education Li Andersson, 32; Minister of Finance Katri Kulmuni, 32; Prime Minister Sanna Marin, 34; and Interior Minister Maria Ohisal, 34

Source: VESA MOILANEN/LEHTIKUVA/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

In Africa, women have risen through ladders of political leadership to become heads of states. These women have defied cultural biases in Africa’s majorly patriarchal culture to lead their countries. Liberia’s Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the first female head of state in Africa and who received a Nobel Peace Prize in 2011 for her efforts in furthering women’s rights is yet another great example of a female African leader. She served for two consecutive terms, battling crises of youth unemployment, ballooning national debt, Ebola scourge, security threats and promoting rights of women. Other great examples include Joyce Banda of Malawi, Ameenah Gurib of Mauritius and Sahle-Work Zewde - who was unanimously appointed President by Ethiopia’s parliament just recently. Saara Amadhila, the current Prime Minister of Namibia served as the minister of finance and is best remembered for minimizing government spending and leading the country in first budget surplus case.

Women’s participation in political leadership is not just at the helm, though. At the moment, half of Ethiopia’s cabinet is comprised of women. In Rwanda’s parliament, women take up 61.1% of the seats.

These are just but a few examples of phenomenal women that have led Africa in different capacities. However, will it be fair to talk about current women in leadership without mentioning those who went before them? There is the late Nobel Peace Prize laureate, Prof. Wangari Mathai who stood up for peace and sustainable development, even when it meant risking her life. The late Winnie Mandela who stood in place for her incarcerated husband and led the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa. Graca Machel Mandela, who was among freedom fighters in Mozambique and a benevolent humanitarian, has continued to gracefully serve Mozambique, South Africa, Africa and the rest of the world especially in advocating for rights of women and children. It is clear that whether in power or in supporting roles, women have contributed immensely towards the leadership of Africa.

In Kenya, for example, affirmative action to promote women representation in public offices is yet to be fully operationalized, with institutions such as the National Assembly failing to implement the two-thirds gender rule in the Constitution. There have been cases of public institutions appointing an all-men board, which begs the question of whether there is a shortage of qualified women to take up some of these positions. Currently, Kenya has six female cabinet secretaries (who, by the way, are excelling at their roles) out of the 21 slots. This goes a long way to show just how deep patriarchy is entrenched in Kenya. Whilst there are programs aimed at empowering women to take on leadership and become financially and socially independent, women are still marginalized. Of what benefit are these programs if the empowered women do not get equal opportunities to exercise their leadership skills?

Perhaps it is worth also reviewing the performance of some of the Africa women that have assumed significant leadership positions and how this has impacted attitudes of Africans towards women leadership.

Left to right: Joyce Banda and Ellen Johnson Sirleaf

Source: UN Photo/Paulo Filgueiras and DON EMMERT/AFP

It is interesting to note that just like their male counterparts, some of the African women who have risen to leadership positions have been subject to a fair share of criticism. For example, while her Excellency Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, did a tremendous job in peacefully leading Liberia after years of horrific civil war, many women have expressed their disappointment in her lack of effort to actively promote women's participation in politics. Consequently, many bills touching on the welfare of women in her country did not receive the much attention and seriousness they ought to have. Mrs. Sirleaf also continues to face allegations of nepotism which include the appointment of her three sons to top government posts as well as corruption scandals that tainted her legacy. On the other hand, Joyce Banda who served both as the first female vice-president and later president of Malawi faced serious corruption allegations including the infamous ‘Cashgate Scandal’ as well as misuse of money she acquired from selling the presidential jet during her tenure.

Nonetheless, the verdict of UN Women is that no single country can claim to have attained gender equality. This calls for a paradigm shift. There is a need to embrace women as equal leaders. As we start a new decade, we need to change tact. Just as we have focused on empowering women, let us learn from Finland and Rwanda and Ethiopia, and other countries that are making progress on this front. Let us ensure that women have equal space on the decision-making table!

‘As Africa’s first woman president, I believe our future leaders must be female’ – Ellen Johnson Sirleaf (First female president of Liberia 2006-2018)

The unveiling of the Building Bridges Initiative report, Kenya’s latest attempt at fostering national unity, was punctuated with an almost frenzy-like reception, especially by the political class.

It came as the political and legal fraternity roamed the country, generously dispending opinions on this much-anticipated document. Some strongly defended and vowed to endorse it even before reading it. Others vehemently opposed it and swore to shoot it down at sight. Interestingly, both sects had no idea of the contents of the report since, until its release, it had been under a tight lid.

In a rather unprecedented turn of events, the political battle lines that had earlier been drawn seemed to suddenly blur when the report became public. The exchanges that now seemed ignorant and myopic, were sheathed and everyone seemed to endorse the report, including the vehement opposers.

The BBI initiative was meant to identify the challenges Kenyans face, and to offer recommendations to help address them. Among its most-talked about recommendation is the proposed expansion of the Executive by reintroducing the Prime Minister position (that was created for convenience of the Government of National Unity, following the 2007/ 2008 post-election violence). This, together with the Leader of Opposition post, an all-inclusive cabinet, and the reconstitution of the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission are meant to address electoral in injustices that Kenya has experienced every election cycle by solving the “winner takes it all” issue. Its other key recommendation is the increasing of allocations to counties to between 35 and 50% of the last audited accounts. Together with other recommendations in the 156-page document, the overarching message is the need for inclusivity and accountability in government.

The report highlights important issues that the country has been sidelining. Major issues like lack of a national ethos, ethnic antagonism, divisive politics, corruption and devolution were highlighted complete with recommendations. If leaders and stakeholders devoted their time, energy, and focus towards implementing these recommendations, Kenya would get back on track towards prosperity.

While the report sells the promise of hope, it is not quite clear whether Kenyans should be optimistic about it since there are various reports like the Ndung’u Land Report and the Truth Justice and Reconciliation Commission Report from many years back have still not been implemented.

Most importantly, the Constitution of Kenya clearly outlines principles by which the country should live by. If Kenyans took dictates of the constitution to heart, there would be no need for a BBI report and its rather unsurprising recommendations.

Other than the structural recommendations on how the government should look like, most of the other recommendations are things any Kenyan is familiar with but chooses to overlook or sweep under the carpet in pursuit of selfish interests. One need not go any further than the nearest shopping center to see this. There will be a boda boda (bicycle taxi) guy riding on the wrong side of the road; a pedestrian littering recklessly; and someone being pickpocketed. There will also be a car over-speeding right after bribing a traffic officer.

In the next day’s newspaper headline - it is likely a scandal or a government official hurling insults at another political leader. Counties, while fighting for a bigger share of the national revenue, struggle to justify this request, given that the little they receive is barely utilized responsibly. Tales of funds misappropriation, unexplained expenditure and questionable receipt records have become a norm.

It is unsurprising that new battle lines are already forming after politicians differed on how the report should be implemented, just days after its launch. That speaks a lot on Kenyans’ character as a nation. There could be many reports like the BBI, but until there is a radical mind-shift among Kenyans, the challenges being addressed won’t be going away anytime soon.